So, if poetry can be so dangerous as to merit its prohibition in Socrates’s ideal republic, can it also be altered, or at least adapted, to merit its exaltation in our postmodern and economically global society? Even Socrates knows that the poet has a raw power to make people at least think and not only to think but also to feel. And this is precisely the point that makes poetry so important. Obviously, lying awake in bed hoping for blue eyes will not advance racial equality. Like how when Pecola Breedlove in Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye desires to become white and beautiful and no longer black and unlovable in a racist society, she lies awake hoping to magically acquire blue eyes. “Then we shall conclude that all poetic imitators, beginning with Homer, imitate images of virtue and all the other things they write about and have no grasp of the truth? … himself knows nothing about, but he imitates … in such a way that others, as ignorant as he, who judge by words, will think he speaks extremely well … he speaks with meter, rhythm, and harmony.”īeyond the fact that poetry deals in untrustworthy imitations, Socrates’s actual concern is that poetry doesn’t offer good examples for people to live by. So, Socrates can’t help defining the poet polemically, since he is concerned unto his death with what is real and not with what is merely apparent. Rather, poetry’s task for Socrates is to make the “real world” of ideas less real-that is, to reduce what is already very real into words and phrases that are only appearances. Poetry’s task is not to take something unreal, like an idea, and then make it appear real, nor is it to “invent” an otherwise un-invented world. Which, however, is the “traditional narrative” that Pedro Erber is after?įor Socrates, poetry is imitation: “a poetic imitator uses words and phrases to paint colored pictures of each of the crafts.” Imitation is of real things, whether of people, professions, ideas, or emotions. This has been a stable attribute of poetry from the first line of Homer’s The Odyssey to the last line of Dean Young’s “Romanticism 101.” So, there is the interesting task of deciding whether to ask a poet (or, more appropriately, a poem) What is poetry? or whether to ask a philosopher (or, more appropriately, a philosophy) What is poetry? Both, it is clear, presume to know. All art is, in addition to its content, a representation of the work of representing. All writing comments upon the act of writing. But Socrates sought to challenge and perfect the mythological ordering of reality-so elegantly depicted by Homer and the poets-by the exercise of reason in the context of dialogue.Īll poetry is a reflection upon poetry.

The cosmic order of the gods, human affairs, necessity and chance, emotions and sentiments, virtue, beauty, and everything distinctly human seemed to be contained within Homer’s universe.

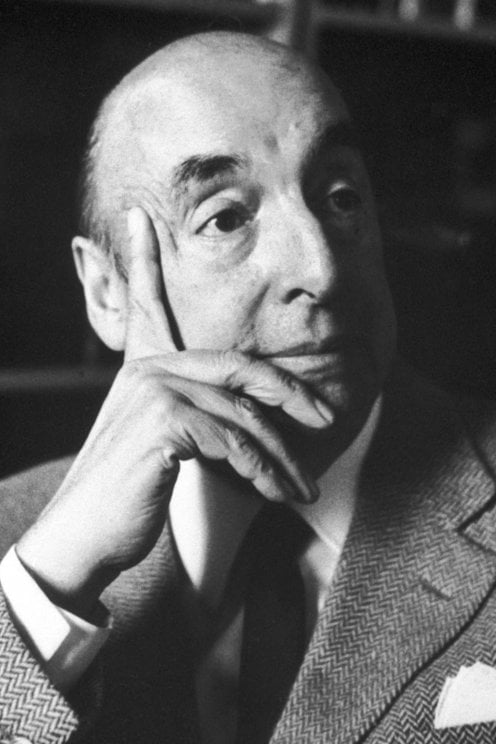

Reflection on our poetic tradition begins in Book X of Plato’s Republic, in which Socrates asks something really fundamental: What exactly is a poet, anyway? Homer had, in Plato’s time, been regarded as the authoritative voice on reality. This question was similarly emphasized during a 2008 seminar, published under the title “Art and Globalization,” which considered Susan Buck-Morss’s essay “Hegel and Haiti.” The Brazilian aesthetic philosopher Pedro Erber remarked halfway through the conversation, “Bringing it back to the question of globalism in art-maybe, instead of trying to globalize something, it is a matter of realizing and recognizing that art and its history are, in fact, already much more global than what one might have been told by traditional narratives.” How can and how does the poet contribute to the political, historical, and economic tradition of their society? Neruda is our evidence his question is our prerogative. The intersection between poetry and politics, between art and economics, is ineluctable, undeniable, and pressing. Leaving behind an undeniably significant poetic legacy, Neruda also left this world a communist, an accessory to the grave human rights crimes of the early twentieth-century Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin. Neruda would pass away in the capital city of his Chilean homeland months after asking himself-and us, who inherit his question-just how, exactly, the poet contributes.

As though he were at once interrogating and acquitting himself, Pablo Neruda concludes his acceptance of the 1971 Nobel Prize in Literature thusly: “But what would become of me if I, for example, had contributed in some way to the maintenance of the feudal past of the great American continent?” (¿ Pero, qué sería de mí si yo, por ejemplo, hubiera contribuido en cualquier forma al pasado feudal del gran continente americano?)

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)